A História da Guerra do Peloponeso, por Tucídides, ainda é uma grande leitura para os tempos atuais, válido tanto para história, estrito sensu, como para relações internacionais, no sentido lato, pois que tratando das más decisões tomadas por Atenas em suas alianças com outras cidades-Estado gregas na luta contra Esparta. Mas, as interpretações feitas a partir da sua obra, como se existisse alguma "armadilha de Tucídides" no caso de uma suposta disputa hegemônica entre os EUA, o poder estabelecido (ou Atenas), e a China, equivocadamente identificada com Esparta (por ser "ditatorial'), refletem apenas a paranoia inacreditável de acadêmicos americanos – no caso, o professor Graham Allison, de Harvard – que se deixaram contaminar (o termo é apropriado, não só pela peste em Atenas, que vitimou o próprio Péricles, mas pela pandemia do século XXI) pela paranoia dos generais do Pentágono (que têm por obrigação ser paranoicos). Essa postura confrontacionista dos americanos – como se eles fossem atenienses agressivos e arrogantes – é sumamente equivocada, inadequada e prejudicial, não só aos dois gigantes da economia mundial, mas a todos os demais países, em especial os países em desenvolvimento, que poderiam se beneficiar com duas locomotivas do crescimento global e das possibilidades de cooperação entre elas, dada sua complementaridade absoluta.

Paulo Roberto de Almeida

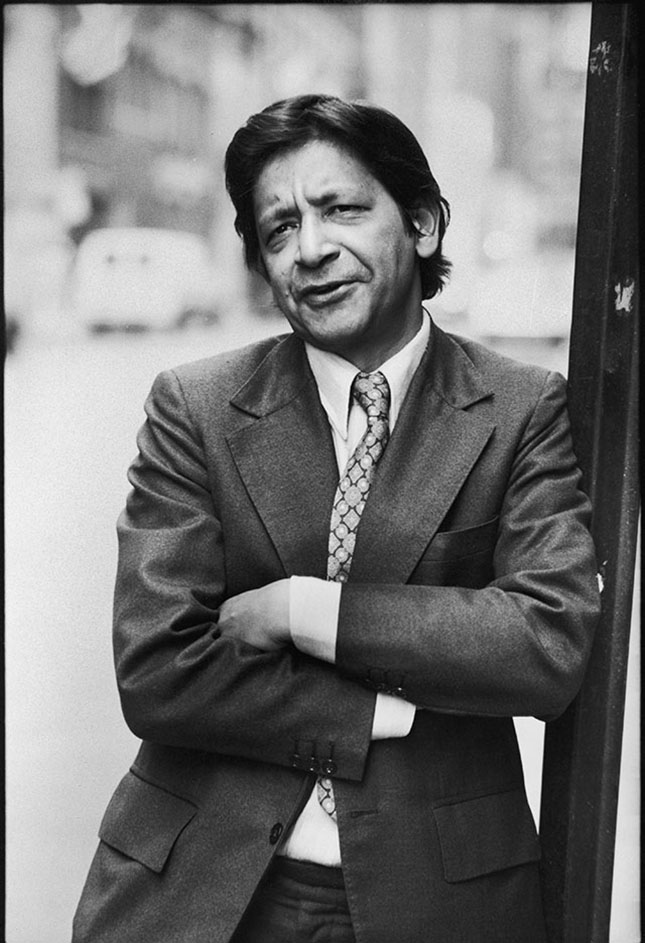

MIGUEL MONJARDINO

Digging Thucydides in Lisbon

China’s rise has led to pat citations of the Athenian historian, but one must truly study his work to understand it.

The City Journal, May 8, 2021

https://www.city-journal.org/digging-thucydides-in-lisbon

At the March 18 meeting of senior American and Chinese officials in Anchorage, Alaska, Yang Jiechi, director of China’s Office of the Central Commission for Foreign Affairs, clarified his country’s position: “The United States does not have the qualification to say that it wants to speak to China from a position of strength.” Xi Jinping’s sobering message to the Biden administration was that the United States can have peace or war. Amid the political fallout of Anchorage came a deluge of references to Thucydides, the Athenian general and historian who wrote The History of the Peloponnesian War in the fifth century B.C. “The Thucydides Moment?” asked the Nikkei Asia Review after the meeting. General Xu Qiliang, vice president of China’s Central Military Commission and the country’s top military officer, spoke about the “Thucydides trap.” Indeed, such references have become almost mandatory since Harvard professor Graham Allison coined that expression a decade ago to warn about the dangers of a contest for supremacy between the U.S. and China.

But Thucydides never wrote about the trap. What he wrote, in the beginning of the History of the Peloponnesian War, was: “In my view the real reason, true but unacknowledged, which forced the war was the growth of Athenian power and Spartan fear of it.” This is one the greatest sentences ever written in political analysis, but it can be interpreted only with reference to Thucydides’s views about power, the nature of the Athenian and Spartan regimes, and the realities of empire, money, political psychology, time horizons, and war. Our current fixation with the “Thucydides Trap” has led to an unfortunate oversimplification of his work.

Thucydides has been hosting the longest-running seminar in international politics, and the price of admission for those who want to enroll in it is simple: you have to read him. Since February, I’ve been doing just that with the class of 2021—I call the students, born in 2000, “the last class of the twentieth century”—of the Institute for Political Studies at the Catholic University of Portugal, where I am a visiting professor. Laura Lisboa, a gifted student who graduated with distinction in physics at Instituto Superior Técnico and then switched to work in political science, is the teaching assistant.

Covid-19 has upended our lives. Since March 2020, I’ve been waiting out the pandemic in Angra do Heroísmo, a World Heritage Site in the Azores, while the class reads Thucydides in their homes across Portugal. Zoom has become indispensable for us—at a price. “I don’t want to sound spoiled,” said a young woman in our first class. “We are healthy and, unlike many, we have food on the table. My point is, up to the beginning of the pandemic, university was about being together. Now, in spite of all this technology, I don’t think we are together at all. We used to talk through the night. We shared ideas in bars and libraries. We went out. Now we look at the same walls every day. Today is just like yesterday. Nothing will change tomorrow. We had to learn how to live isolated. It’s been really hard to find the motivation to study and write. When will we be together again? I miss going to live concerts.”

I feel for them. University shouldn’t be like this. I’ve had to reconsider everything about the content and rhythm of education in the digital world, though two decades of work in television have proved helpful.

While Covid-19 cannot be compared to the plague that devastated Athens from 430–427 B.C., it has helped the class appreciate the power of Thucydides’s description of a contagious-disease outbreak in the middle of a war. Among the many casualties of this plague were Athens’s senior statesman Pericles, his sister, and his two sons. The class examined François-Nicolas Chifflart’s Pericles at the Death Bed of His Son and Michiel Sweerts’s Plague in an Ancient City and read his funeral oration to the sound of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony. I asked: was Pericles, who devised a military strategy based on attrition against Sparta and its allies, responsible for the plague and its consequences? The students didn’t reach a consensus. “The way I see it, the war with Sparta was inevitable,” said one. “The plague was not something he could have predicted. Events surprised him. I don’t think he is responsible for this.” “I disagree,” argued another. “I believe he is washing his hands of the responsibility here. This is not leadership. If I was at the assembly, I would trust him less after this.”

Athens agonized over the decision, but eventually struck a defensive alliance with Corcyra (now Corfu). The Athenians believed that the island—with its privileged geopolitical position in the northwest and a powerful navy—would enhance Athens’s security and help the city-state maintain a favorable balance of power with Sparta. Events then took a surprising turn. Instigated by Corinth, an ambitious and risk-taking city, revolution and a bloody civil war consumed Corcyra. Sparta and Athens intervened.

In his powerful account of these events, Thucydides gives his opinion about the drastic changes in values that the civil war brought about. It is essential reading for any political education; as the class read, Schubert’s “Ständchen” D957played in the background. “Why did Sparta withdraw its navy from Corcyra?” asked one perplexed student. “They were winning here. What’s wrong with this Alkidas, the Spartan admiral?” “This is really shocking,” said another. “I mean, fathers killing sons. And the Athenian admiral does nothing. He could have put an end to this horror. This looks like something that Sparta would do, not Athens.” “Perhaps,” said another, “but Corcyra’s geopolitical location is really important for Athens. I believe this is about necessity in war. Just like the Spartans in Plataea. The Athenian fleet is there to deter more foreign interventions and give time to the popular party in Corcyra to turn the civil war in their favor.” “Yes,” observed one student, “but this is not what Athens had in mind when it accepted the alliance. Now they will have to commit more naval forces in the northwest.” “What I find puzzling is how unstable Corcyra is politically,” said another. “How can they be a good ally of the Athenians?”

War, as Thucydides reminded us, is a “violent school.” Francisco Goya, the Spanish painter, knew this too. We discussed his masterpiece El tres de Mayo en Madrid, and some of his drawings and etchings currently in exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Civil strife and the powerful emotions that it elicits pose the greatest dangers to any society.

When our seminar drew to a close, we had covered plenty of ground. Our first deep dive into Thucydides’s work, in February, was unsettling. “Do we have to know all this?” asked one student after reading the first paragraphs of the History of the Peloponnesian War and looking at the maps. “I never heard about many of these cities.” “The political context is very confusing,” observed the aide-de-camp of the class. “We don’t live in Thucydides’s time.” Quite right. But there is something about the way Thucydides writes that progressively draws readers into his work, into the dark pit of a long and destructive war. By the end, students had chosen their sides in the war: some Athenians; others Spartans; a few believing that Corinth was right in challenging Athens and pressuring Sparta to step up in defense of its allies; others curious about Persia, the superpower of the time. (As far as I know, Corcyra has no supporters. “They are just like Hannah Montana,” argued a student, tongue in cheek. “They want everything and don’t understand that all of this happened because of them.”) Thucydides became personal to them.

“I have a question,” said a pro-Athenian student. “If Pericles was alive at the time, would he allow this level of violence in Corcyra? I was really shocked by this.”

“What do you think?” I asked.

“I don’t think so,” he replied. “I doubt he would be so brutish. This is not his Athens. Something has changed.”

Yes, up to a point. War happened. That changed everything. Athens was not the same after Pericles’ death in 429 B.C., but the city had been an ambitious imperial democracy for decades. The Athenians always feared revolts by their allies. In his last speech, Pericles was blunt about it: empire was “like a tyranny—perhaps wrong to acquire it, but certainly dangerous to let it go.”

Thucydides, an Athenian and senior military officer who witnessed the rise and fall of his extraordinary city, wrote to tell us that the world is difficult, ambiguous, and complex. Politics and strategy possess too many variables; a few are interdependent. To quote one of his paragraphs to try to explain current events—such as the competition between the U.S. and China—is not enough. The Athenian general wanted us to read his work and to argue with him. That’s why I’ve looked forward to my conversations with the class of 2021 about The History of the Peloponnesian War. Many years from now, when their sons and daughters ask them what they read at university, the members of the last class of the century will be able to say, “I read Thucydides at the Catholic University.”

Miguel Monjardino is a visiting professor of geopolitics and geostrategy at Portuguese Catholic University.

Photo by Sunil Ghosh/Hindustan Times via Getty Images

City Journal is a publication of the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research (MI), a leading free-market think tank. Are you interested in supporting the magazine? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and City Journal are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).